Carel Weight is simply one of my favorite painters of all time. His imagery is steeped in isolation and anxiety, and he paints the kind of psychologically disturbing and haunting images that I adore. Born in London in 1908, he worked as an artist and teacher in England throughout his adult life, and although he exhibited his paintings regularly, he kept a comparitively low profile as an artist. At one point he had the opportunity to take the route of exclusive gallery representation, which would have increased his wealth and fame significantly, but he opted to hold ambition in check so that his friends might still be able to afford his work. His paintings are not well known internationally, which is a loss for those of us who delight in idiosyncratic vision. However, UK blogger ‘I Love Total Destruction’ has an entry on him here, and since I began writing this entry months ago, Paul Behnke blogged about Carel Weight here, so there are contemporary artists who hold him in esteem and there is the hope that Weight’s work will reach a wider audience.

Weight’s paintings are captivating for many reasons - his color sense is perfectly in tune with his mysterious imagery, his realism is modified by the emotions of fear and anguish, and his compositions reveal a deep understanding of 2-d image structure. Formally, he was an accomplished painter and a teacher to some of England’s best-known contemporary artists, including David Hockney, whose 1968 portraitAmerican Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) at the Art Institute of Chicago shares a similar sensitivity to uncomfortable personal relationships that was Weight’s great strength.

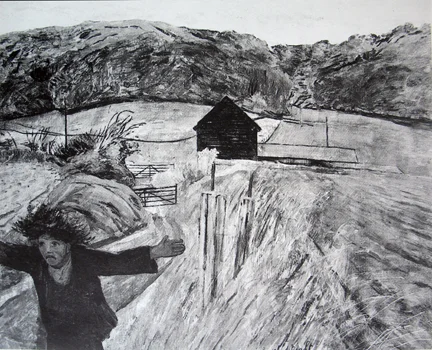

It isn’t mastery over materials that keeps me looking at Weight’s work though - it’s his crazy, compelling, haunted voice, and how he gives us a frank look at the unknowable world of individual emotional lives. He paints human beings in almost every canvas, and gives us portraits that are at least as much about the personality of the sitter as they are about a depiction; see his riveting portrait of Orovida Pissaro, the French Impressionist’s grand-daughter, whom Weight referred to as ‘magnificent.’ 1 Weight also painted people in the midst of tense and theatrical situations, showing victims fleeing aggressors, people in flight from burning buildings or flood, and impending traffic disasters. Many of his canvases show people sitting or standing among one another yet in unmistakable isolation, such as the 1965 canvas The Silence at the Royal Academy of Art. Of all his paintings, the ones I love the most show people and apparitions together as a way to underscore the emotional complexities of the painting. Weight incorporates apparitions into his paintings with great success as a content vehicle when they’re commonly used a device, overt or witless. To me, that’s quite an accomplishment.

I can’t tell you when apparitions first appeared in his paintings; a large number of his works were eradicated when his London studio was bombed during WWII, early in his career. However, a broad overview of Weight’s work from the beginning of his career as an Official War Artist to his lengthy tenure at the Royal Academy of Art shows that his figures were both solid and diaphanous during the second World War, by 1942 at least.

Carel Weight, Hammersmith Nights, Oil on board, approx. 6” x 8.5”, 1942, © the estate of Carel Weight

Weight stated unequivocally “I have always been terrified by the idea of ghosts.” Terrified by an idea is one thing, but is there evidence that ghosts were real for him? The only literal ghost I’m aware of in his work is found in “The Presence,” a canvas from 1955, depicting a scene at Bishop’s Park at dusk. On seeing this canvas, one Londoner told Weight that she had seen that same apparition there. Weight admitted that he liked “to weave fantasy into the context of quite ordinary things” but then also said that the woman made him think there was “a likelihood that the ‘presence’ is not just a figment of my own imagination.” 2 This ghostly presence is found in the bottom center of the canvas; she is a transparent figure wearing a headcovering and holding what appears to be a basket, with her full-length dress rendered in light turquoise, picking up the shade of the park bench behind her.

Carel Weight, The Presence, Oil on Canvas, 1955, 47.5” x 80”,© the estate of Carel Weight

I’ve found no source that can state if real-world experience was at the heart of Weight’s other painted apparitions. That would be interesting to know because of how he depicts them; they are matter-of-fact, rendered without gore in the case of the haunted, or syrup in the case of the angelic.

In some works, Weight makes apparitions exist as a sort of natural conclusion; they aren’t by themselves terrifying or gory, but it’s their presence as something natural and ordinary that gives pause. Most often, people describe apparitions with the word ‘otherworldly,’ but in Weight’s case it doesn’t apply, as these isolated, ethereal beings seem the most unaffected occupants in the world. In ‘The Departing Angel,’ Weight is simply showing us an afterlife extension of the reality of isolation among the living:

Carel Weight, The Departing Angel, 1961, Oil on canvas, 36” x 36”

© Royal Academy of Arts, London, Photographer: John Hammond

Weight’s departing angel is neither luminous nor particularly hopeful, but has a resigned appearance that tells me that the artist’s outlook to the end of time remained bleak. His apparitions are painted with a sense of fluidity, and in contrast I notice how his living figures appear immobilized, as though they suffer some kind of emotional quarantine. They brood, they worry, and they have a sickness of spirit that keeps them disengaged with each other as well as the world around them. In this same painting for example, one would think that a young woman who has just ended a visitation from an angel might be feeling some sort of ecstasy, but here she calmly remains seated, as though she’s recollecting something mundane.

Weight often portrayed living figures in resignation and grief, highlighting their sadness with closed body language like folded hands resting in the lap. The painting ‘Fallen Woman’ doesn’t include an obvious apparition but shows a dejected woman seated in a dark alcove next to two empty terra cotta pots and behind a bare trellis that figures as a sort of cage. She has a mysterious circle inscribed above her head; it’s a ring of black on the brick, and there’s a shadow of this ring shape to the right. From my vantage point as a painter, these circles seem to be the first attempts at head placement on the part of the artist, so they function as a type of phantom for me.

Carel Weight, Fallen Woman, 40” x 23”, 1967, © the estate of Carel Weight

The most typically angelic figure that I know to exist in his paintings is found in ‘The Battersea Park Tragedy,’ which commemorates children who were killed when a car jumped the track on an amusement ride. The grieving woman reflects on “the closeness of tragedy, the bolt from the blue.” 3 But the sobbing angel -possibly one of the children- is unable to ascend, bare feet trapped at the ankles in the red roller-coaster track.

Carel Weight, The Battersea Park Tragedy, Oil on Canvas, 72” x 96”, 1974, © the estate of Carel Weight

Memories, loneliness, and internal fears and terrors are present in his work, and apparitions function as the uniting factor between internal and external worlds. A jarring skeletal form clutches a female figure from behind in the painting ‘Sunshine and Shadow,’ yet doesn’t seem to terrify her; it merely impedes the woman’s movement so she seems trapped by a memory of her past. Her innocence is portrayed by nudity and sunshine in the top half of the painting, where the young figure is oblivious to an ominous form watching her from the shadows:

Carel Weight, Sunshine and Shadow, Oil on Canvas, 21” x 13”, 1968,© the estate of Carel Weight

In ‘Thoughts of Girlhood,’ an old woman fixed in a metal chair recalls her youth, with the memory of her buxom figure an integral part of her lush garden landscape. Both the living woman and her fond memory supply us with a blank emotional landscape, perhaps suggesting that the subject never really found happiness in her long life, except perhaps in the pleasures of her garden:

Carel Weight, Thoughts of Girlhood, Oil on Canvas, 36” x 48,” 1968, © the estate of Carel Weight

The most disturbing people in Weight’s paintings never seem to be the apparitions oddly enough, but the running children who are terrified, screaming, and painted mostly in the lower third of the canvas, often toward a corner, in a desperate effort to flee the confines of the scene. I’d like to think that Weight gives these young, living souls some hope in that they often extend beyond the edge of the canvas, partially escaped.

Carel Weight, Frightened Children, Oil on canvas, 36” x 48”, 1981, © the estate of Carel Weight

Carel Weight, The Invocation, Oil on Panel, 20” x 24”, 1976, © the estate of Carel Weight

1. Mervyn Levy, Carel Weight (Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1986), 64.

2. Levy, Carel Weight, 23.

3. Levy, Carel Weight, 31.

_____________

Courtney, Carol. “Obituary: Professor Carel Weight.” The Independent, August 15, 1997. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-professor-carel-weight-1245500.html

Levy. Mervyn. Carel Weight. Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1986.